Whether it’s just a knife & knowledge, or 30 kg of the latest hi-tech wizardry, all hunters have firm ideas about the bare minimum in gear needed to survive in the bush, as Don Caswell explains.

I consider myself a minimalist. No more so than in what I elect to carry on me when I am out hunting. My hunting buddies often carry a lot more gear than I do and are always on the lookout for new items of the latest gee-whiz gizmos. They spare no expense and do produce some amazing bits of kit at times.

When it comes to absolute, comfortable minimisation though, my aboriginal hunting companions have it mastered. A good example of that comes from some years back when I took off on a buffalo hunting trip. It was a few hundred kilometres of dirt track to a remote community where I collected my regular hunting buddy, Mickey.

He was barefoot and bare-chested when I pulled up and surprised me by jumping straight into the cab and declaring, “Let’s go!”. I looked at him for a few seconds to see if he was kidding, but it was clear he was serious. I said, “Mickey we are going to be out bush for four or five days. Don’t you need some gear to take with you?” He thought about that briefly, nodded in agreement, and returned to his house.

He was only gone a minute and when he returned he was equipped with everything he needed; a shirt, a billy, a knife, a box of matches and a packet of smokes!

It goes without saying that Mickey is a master bushman with an incredible knowledge of the bush. To him, the wilderness is both a well-stocked grocery store and a hardware shop. As I know and have seen, Mickey can survive comfortably in the bush with no equipment at all. To him a knife and a box of matches are useful luxuries, but not essential.

When you are bush-bashing with a vehicle then you can carry a plenty of gear and lots of luxuries. If you are back-packing on Shank’s Pony, then you need to be a lot more pragmatic. Nevertheless, I am at times amazed at what people consider essential and tote around with them on a foot safari. Clearly it is very much a case of personal preferences and priorities, not right and wrong.

There are a few things that are essential when considering an extended hike in the wilderness. I would say the list starts with good hiking boots. They will give you every chance of getting in and out under your own steam – which is the ultimate goal of the exercise. Be prepared to pay for good quality boots. You may be lucky and find a budget pair that is perfect for you. I spent quite a bit of money buying lower range hiking boots over the years and was continually unhappy with the result.

When I finally convinced myself to shop in the higher priced section I reckon my annual spending on boots reduced significantly. Instead of buying a new pair of budget-priced boots every year, I now expect to get 5 or more years of comfort and reliability from each pair of the higher priced variety. It pays to visit the larger specialty trekking and camping shops and try a variety of boots on for fit and comfort before committing.

Another item of footwear we all carry which is really useful in the tropics, is a pair of thongs each. At the end of the day when camped up it is great to relax in those and let the hiking boots air.

The other essential is water. You need to be confident of finding water and carrying enough to get you between watering points. This is particularly so in the tropical north where the exertion of outdoor activity in the warmer months (not necessarily the hottest, which are best avoided) may require as much as 10 litres per person per day. In cooler climates a litre or two may be enough to get you through a day. This is an important point to note for folks not used to the tropics. What works perfectly well down south could end up killing you in the far north.

There are a number of distressing examples of just that happening to cold climate European tourists who arrived in the NT for a dream holiday and did not survive their first day due to dehydration and heat stroke.

I consider the next most important consideration is a risk assessment of just what could happen on your trek and how the group would deal with that. Snake bite, attack by wild animals, sprains, broken bones, dehydration, even death are unfortunate possibilities for those folks who head off into the wilderness. I don’t consider it feasible to carry a lot of extra gear just in case of such events. But the group must consider what they would do if something untoward does occur.

It is best to work this out before you set off and have a clear plan. If you don’t do that and something serious occurs then the group is quite likely to make a bad choice under duress and put more people in danger.

Close to essential is a good night’s sleep. When on an extended foot safari it is important to select a good spot to sleep each night. I look for a soft, sandy patch near a tree. In selecting the tree, its shade value is not relevant. My concern is having somewhere safe to scurry behind, or up, should a wild animal come calling. Other things to consider are making sure there are no resident ant or wasp colonies making use of the immediate vicinity. Also check for any dead branches that might fall on to you.

Even a relatively small branch can cause surprising injuries in falling from a height. There have been well publicised, and tragic, cases of Aussie campers being killed by falling branches, so it is a real risk.

You might ask why I would want to hide behind a tree when there are heavy calibre rifles in camp? The only thing more dangerous than a nocturnal visit from a boar, buffalo or scrub bull is someone firing off a 458 Winchester Magnum in the dark. Think about that for a moment.

Sleeping on the ground need not be an uncomfortable experience. There are a few things to consider. The key is to scratch out a bit of a hollow to accommodate your hip when you roll onto your side. A light blanket is needed, even in the top end. On sandy ground a mattress is not essential. On harder ground a thin, expanding sleeping mat is most useful in getting a comfortable night. For a pillow I generally sleep on my rolled-up clothes. Alternately, if the mosquitoes are not a problem I use my bundled up mossie net as a pillow and let my clothes air over night.

A lightweight mossie net can save you from a restless and disturbed night’s sleep. I have learnt that the hard way on a number of occasions when I thought there would not be many mosquitoes around and I elected to save weight in my backpack.

Food is an essential of course. Even when planning to live off the land it would be wise to carry some compact satchels of hiking food in case Mother Nature does not provide. Again, aboriginal abilities at hunting and gathering are really something to behold. A year or two ago my adult boys joined me and my old mate Mickey on a walkabout in a very remote part of Arnhem land. We had left it a bit late for that and it was already pretty hot in late October when we set out. As a result we only moved about early and late and spend the middle part of the day cooling off in shallow sections of river.

We had the bare minimum of food and were planning on shooting wild cattle and buffalo for meat as we travelled. As luck would have it, game was a bit elusive for the first few days. That was not a problem for Mickey. We had brought along a hand line and some hooks for fishing.

Mickey walked about fifty metres down the river to a deeper hole. Along the way he grabbed a passing grasshopper for bait. The line was not in the water more than a minute when he pulled a good size tarpon out onto the bank. With pieces of fillet from the tarpon he in no time landed a brace of fish and had them threaded onto a stick. There were black bream, tarpon, saratoga, barramundi and catfish in abundance, but we took only what our immediate needs required.

A shallow hole was dug and a fire lit in it. Pieces of ant nest were added to provide a heat source for the cooking process. While the fire was burning down to coals Mickey gave us a lesson in gathering from the creek. In short order we had a billy of small clams and also a collection of yam-like roots from the water plants. The fish were laid on bed of leaves on top of the coals and hot pieces of ant nest.

The make-shift oven was covered with pieces of the ever useful paperbark and then a layer of sand was delicately spread on top to seal in the heat. A small fire was lit nearby and billies brought to the boil. The roots and clams were then added to the boiling water.

A touch test revealed that the layer of sand covering the cooking fish was getting hot. That indicated that the fish was done. The sand was swept off and the paperbark carefully pealed back to avoid spilling any grit onto the steamed and smoked fish. The smell was delicious. The leaves, specifically selected and not eucalypt, had added a lovely herb and light smoke flavour to the fish, which was cooked to perfection. Our feast of fish, clams and yam was served up on platters of paperbark and very nice it was too.

Survival kits are a very personal item, ranging from nothing right through to some pretty extensive collections of gear. Survival kits should not be confused with your camping equipment. To me a survival kit is a small, compact kit that you carry with you when you leave camp to go hunting, or exploring. It is there in case you can’t make it back to camp and have to spend a night, or longer, in the bush alone. That could happen through unexpectedly bad weather, getting lost or through injury or sudden ill health. In such cases the ability to light a fire, shelter from the weather and take a dose of Panadol are invaluable, perhaps even life saving.

There is no right or wrong in the choice of a survival kit other than that it makes enormous sense to carry one. My belief is that it should be with you when you walk out of camp, either in your backpack or on your belt. This is essential if you are out and about alone or with a companion, less so with larger groups. I don’t bother with food in my survival kit at all because it is no problem for the average outdoors adventurer to go days without food should circumstances arise.

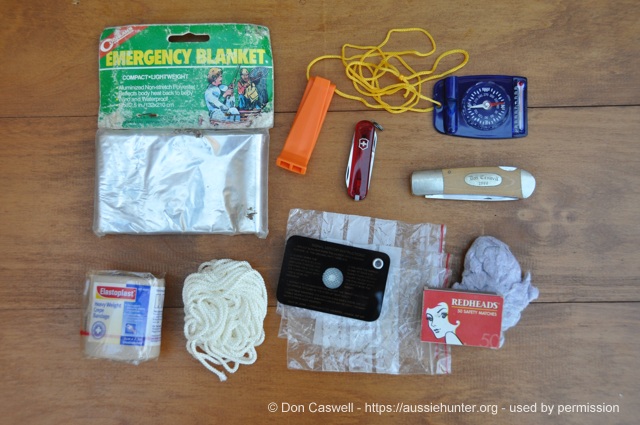

My concerns are at being either injured or lost and the contents of my survival kit reflect that. I have a foil blanket for retaining body heat and shelter from sun and rain. Bandages and Panadol tablets are there for injury. Matches and lint are there for starting a fire. I have a couple of wads of lint taken straight from the laundry clothes drier. I keep the lint in small zip-lock plastic bags. I also have a larger, folded-up plastic bag which can be used to collect and store water in an emergency. There is ten metres of light but strong cord and a signal mirror, compass and whistle. It is all packed into a compact camera case.

There are lots of excellent books and guides, not to forget TV shows, on camping and survival available and these too can be of great interest and educational for those who enjoy trekking and hunting in the more remote wilderness.

© Don Caswell 2011

About the author

Since 1981 Don Caswell has been a freelance writer, photographer & illustrator. Don is the author of hunting stories and the provider of technical shooting information. Don an independent reviewer of hunting, shooting & outdoors products, in addition to being a blogger & webmaster with Facebook & Instagram presence. Don is also a senior writer for the Sporting Shooters Association of Australia (SSAA) and his articles appear regularly in their publications. This article was originally published in the SSAA in April 2014.

Visit Don Caswell's Aussie Hunter Website here